The Carmelite Rule Commentary

The Carmelite Rule

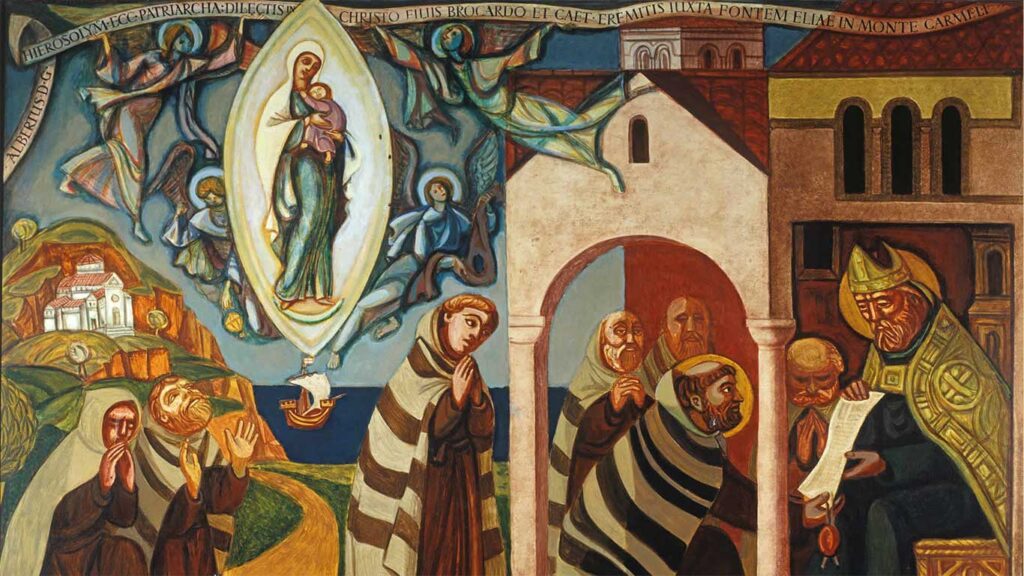

1 ] Albert, called by the grace of God to be Patriarch of the Church of Jerusalem, greets his beloved sons in Christ, B, and the other hermits living in obedience to him near the spring on Mount Carmel: salvation in the Lord and the blessing of the Holy Spirit.

Commentary

1 ] The Carmelite Rule begins like a formal medieval letter with a salutation and a blessing. Albert, Patriarch of Jerusalem, greets the hermits living on Mount Carmel together with a leader. Albert’s opening words would remind readers of one of the letters of St Paul. This leader is simply called ‘B’ in the text since his precise identity is unknown (cf chapter 22). The early Carmelites were dwelling near a spring on Mount Carmel, a mountain range, a place, from which they came to derive their name. In time both Mount Carmel and the spring near which the first Carmelites settled became powerful symbols for the Carmelite understanding of the spiritual journey as transformation in Christ.

2 ] Many times and in different ways the holy Fathers have laid down that everyone – whatever be their state in life or the religious life chosen by them – should live in allegiance to Jesus Christ and serve him zealously with a pure heart and a good conscience.

2 ] The call to holiness is universal. No matter what our status in life we must be centred on Christ. Living in allegiance to Christ (see 2 Cor 10:5) took on feudal overtones in medieval times; it suggests that Christians are servants of Christ, belonging to him as their Lord and protector. But purity of heart becomes the key emphasis for Albert because it alone enables us to open up to God and helps us to come to see the world as if with his eyes (see Catechism of the Catholic Church 2519).

3 ] Now then you have come to me seeking a formula of life according to your purpose, which you are to observe in the future.

3 ] The early Carmelites have taken the initiative in approaching Albert as the representative of ecclesiastical authority. They are concerned to consolidate their position, to plan for the future and, furthermore, to be of service to the wider Church community. Note how Albert is being asked to write them a rule (here called a ‘way of life’ or formula vitae) based on how the hermits were already There is, therefore, already a sense of the Carmelite Rule as a living text, the putting into words of a way of living (propositum), intended to inspire others to live the way of Carmel into the future.

4 ] The first thing I lay down is that you shall have a prior, one of yourselves, chosen by the unanimous consent of all, or of the greater and more mature part. All the others shall promise him obedience fulfilling it by deeds, as well as chastity and the renunciation of property.

4 ] The Rule proposes a particular model of leadership among Carmelites. A prior is to be elected and remains one of them, a first among equals. Carmelites are to pledge obedience to their prior. Ultimately such obedience is a sign of one’s fidelity or allegiance to Christ, since later, in chapter 23, Carmelites are encouraged to honour their prior and ‘rather than thinking about him, you are to look to Christ who set him as head over you’. The explicit reference to chastity and poverty as fulfilling (along with deeds) one’s obedience to the prior was added in a later revision of the text.

5 ] You can take up places in solitary areas or in sites given to you, one suitable and convenient for your observance in the judgement of the prior and the brothers.

5 ] ‘The prior and the brothers’ becomes a constant refrain throughout the Rule of Albert. Chapter 5 is a later addition to the text and witnesses to the expansion of the Carmelites in Europe. It makes provision for them to take up residence in solitary places or in other places given to them. All of this is at the discretion of the prior and the brothers who together discern the suitability of locations for foundation. It was this provision that enabled the hermit-brothers of Carmel to become friars, ultimately, ‘a contemplative fraternity in the midst of the people.’ (Constitutions 1995).

6] Moreover, taking account of the site you propose to occupy, all of you are to have separate cells; these are to be assigned by the prior himself with the agreement of the other brothers or the more mature of them.

6 ] The key value of a life of solitude lived in community is made manifest in Albert’s provision for a separate cell for each Carmelite. Once again, the prior and the brothers agree on the allocation of cells. Such a provision contrasts with those communities of monks who sleep in dormitories. The individual cell becomes a defining characteristic of the Carmelite way of life. For the Carmelite imagination the cell becomes a locus (‘a place’) for encounter with God.

7] You are, however, to eat in a common refectory what may have been given to you, listening together to a reading from holy scriptures, if this can conveniently be done.

7 ] Initially we know the early Carmelites lived strictly as hermits, taking meals in their individual cells. This later revision of Albert’s text requires each Carmelite to eat in a common refectory. This is but one way in which individual Carmelites are called to move out beyond themselves and to share with others. And just as the Carmelite receives bodily nourishment in the common refectory, he also receives spiritual nourishment in listening, along with his brothers, to readings from scriptures. Bodily and spiritual nourishment go together.

8] No brother is permitted to change the place assigned to him or exchange with another, unless with the permission of the prior at the time.

8] This chapter is a mark of how seriously the early Carmelites took the allocation of an individual cell to each hermit. Even in the spiritual journey, the far-off hills are greener; a brother might think, if he had another cell, how much more satisfied and holy he could be.

9] The prior’s cell shall be near the entrance to the place so that he may first meet those who come to the place and everything afterwards may be done as he wills and decides.

9] Carmel is from the very beginning a place of welcome. The prior’s cell is to be near the entrance so he can greet all those who come to visit, so he can receive pilgrims in a fitting manner and discern the initial suitability of those who wanted to join the brotherhood. Once again, the way of Carmel is both a journey within and a moving out from the centre.

10] All are to remain in their cells or near them, meditating day and night on the law of the Lord and being vigilant in prayers, unless otherwise lawfully occupied.

10] Chapter 10 clearly echoes Psalm i: ‘their delight is in the law of the Lord, and on his law they meditate day and night’. This chapter of the Rule expresses a key aim of the Carmelite life: that of praying unceasingly (see i Thess 5: 17). The idea of keeping vigilance is an echo of 1 Peter 4:7 and places the spiritual life of the Carmelite within the perspective of the return, or Second Coming, of Jesus. The injunction to remain in one’s cell must, however, always be read alongside those chapters of the Rule which deal with fraternal life, with listening to the Word of God along with the brothers in the refectory, with the celebration of the Eucharist and with work. The cell, the oratory, the refectory and the ministry of welcome are all part of the Carmelite vision of a solitary life lived in common.

11] Those who have learned to say the canonical hours with the clerics should do so according to the practice of the holy Fathers and the approved custom of the Church. Those who do not know the hours are to say the Our Father twenty-five times for the night office – except for Sunday and solemn feasts when this number is doubled, so that the Our Father is said fifty times. It is to be said seven times for the morning Lauds and for the other Hours, except for Vespers when it must be said fifteen times.

11] Chapter 11 of the Rule of Albert attests to the importance of the celebration of the Liturgy of the Hours in the daily life of the Carmelites. It makes practical provisions for those who are unable to do so, perhaps because of illiteracy. Commentators generally agree that at first the Psalms or Hours were probably celebrated by Carmelites individually in the privacy of their cell.

12] None of the brothers is to claim something as his own; everything is to be in common and is to be distributed to each one by the Prior – that is, the brother deputed by him to this office – having regard to the age and needs of each one.

12] The renunciation of property has already been mentioned (chapter 4). Here the importance of such renunciation is underlined. Goods held in common are to be distributed by the prior or his deputy. The Rule is sensitive to the fact that individuals may have different needs. The prior should, in other words, treat everyone according to their circumstances, but not necessarily in the same way. Some will always need more than others.

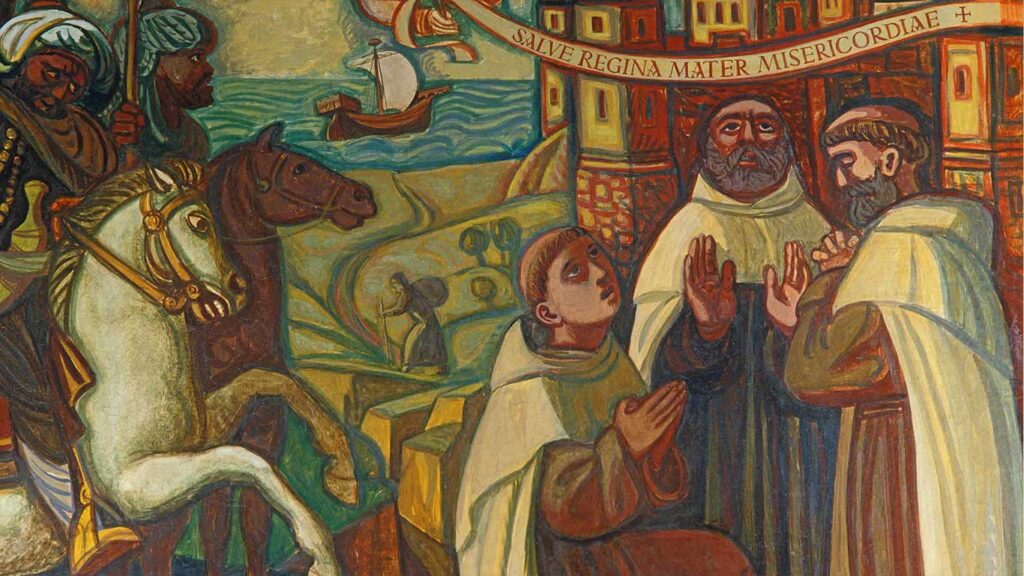

13] You may have assess or mules according to your needs and some provision of animals or poultry.

13] This is a later provision which reflects the fact that the hermits on Mount Carmel did need to travel, moving outwards from their settlement. The means are modest, unlike horses which were for the rich.

14] An oratory is to be built as conveniently as possible in the midst of the cells; you are to gather daily in the morning for Mass, where this is convenient.

14] Chapter 14 of the Rule of Albert is a key text in the Carmelite tradition, emphasising as it does the centrality of the Eucharist. Here remaining in one’s cell is balanced and complemented by gathering daily for Mass. We know from other sources that the early Carmelites named their oratory after Our Lady.

15] On Sundays, or other days if necessary, you shall discuss the welfare of the group and the salvation of souls; at this time excesses and faults of the brothers, if such come to light, are to be corrected in the middle way of charity.

15] Chapter 15 points to two key elements of the Carmelite way: discernment and dialogue. Provision is made for regular meetings of the community to discuss its common aims, to address practical and spiritual matters as well as problematic behaviour on the part of the brothers. All this is to be accomplished in a spirit of open dialogue and in a spirit of charity.

16] You are to fast every day except Sundays from the feast of the Exaltation of the Cross until Easter Sunday, unless illness or bodily weakness, or other just cause counsels a lifting of the fast, since necessity has no law.

16] The next two chapters of Albert’s Rule deal with fasting and abstinence which is undertaken both as a penance and as a preparation for the celebration of major religious feasts. This practice was similar to that followed by other orders. Once again, a spirit of common sense prevails as Albert’s Rule allows for exceptions. The statement: ‘necessity has no law’ is a standard expression of ancient Roman law.

17] You are to abstain from meat unless it is to be taken as a remedy for illness or bodily weakness. Since you must more frequently beg on journeys, in order not to burden your hosts you may eat food cooked with meat outside your own houses. At sea, however, meat may be eaten.

17] The dispensation allowing for meat to be consumed while on a journey and while travelling at sea was added to Albert’s Rule in 1247 and is further evidence of the expansion outwards of the Order. The wording of this chapter was borrowed from the Dominican Constitutions.

18] Since human life on earth is a trial and all who want to live devotedly in Christ suffer persecution, your enemy the devil prowls about like a roaring lion seeking whom he might devour. You must then with all diligence put on the armour of God so that you may be able to stand up to the ambushes of the enemy.

18] Chapter 18 sees the beginning of a new ‘section’ of the Rule of Albert wherein he spells out the implications of living a life in allegiance to Jesus Christ. For the Carmelite, living ‘in allegiance to Jesus Christ’ is envisaged in terms of a battle with the powers of evil both inside and outside ourselves. In this and succeeding chapters of the Rule there are clear echoes of the New Testament, particularly the letters of Paul. While the militaristic language and imagery would have resonated with the experience of the early Carmelites, living as they did in the era of the Crusades, here such imagery is given spiritual significance. Carmelites are to put on the amour of God to withstand the forces of evil (Eph 6:11,13). Wearing God’s armour is closely linked to the idea of living in allegiance to Jesus Christ. St Paul in 2 Cor 10:4-5 speaks of the ‘arms of warfare’ and ‘walking in the footsteps of Jesus’. Representing the desert tradition, John Cassian, when questioned by a monk who complains he cannot master his thoughts and imaginings, uses the image of the soldier who puts on the armour of God to fight the battle of the Lord (Collatio 7:5). The image of the devil as a prowling lion is taken from 1 Peter 5:8.

19] Your loins are to be girded with the belt of chastity; your breast is to be protected by holy thoughts, for the scriptures says, holy thoughts will save you. Put on the breastplate of justice, so that you may love the Lord your God from your whole heart, your whole soul and your whole strength, and your neighbour as yourselves. In all things take up the shield of faith, with which you will be able to extinguish all the darts of the evil one; without faith, indeed, it is impossible to please God. The helmet of salvation is to be placed on your head, so that you may hope for salvation from the one Saviour, who saves his people from their sins. The sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God, is to dwell abundantly in your mouths and hearts. So whatever you have to do, is to be done in the word of the Lord.

19] Albert continues the theme of donning the armour of God which has six parts: the belt of chastity, the tunic of holy thoughts, the breastplate of justice, the shield of faith, the helmet of salvation, the sword of the spirit are based on Ephesians 6:10-17. First we should note that it is God’s armour. All the armour is for protection except for one offensive weapon, the sword of the spirit. With God’s armour our deepest human feelings are protected (belt of chastity). We can be attacked by evil and so we need the protection of holy thoughts. Justice will enable us to love, faith will protect us from what is not God. Salvation keeps us in the sphere of God. The helmet of salvation and the sword of the Spirit are both images taken from Ephesians 6:17.

20] You should do some work, so that the devil will always find you occupied and he may not through your idleness find some entrance to your souls.

In this matter you have both the teaching and the example of Blessed Paul the Apostle; Christ spoke through his mouth; he has been set up and given by God as a preacher and teacher of the nations in faith and truth; in following him you cannot go wrong.

In work and weariness, he said, we have been with you, working day and night so as not to be a burden to you; it was not as though we had no right, but we wished to give ourselves as a model for imitation. For when we were with you, we gave this precept: whoever is unwilling to work shall not eat. We have heard that there are restless people going around who do nothing. We condemn such people and implore them in the Lord Jesus Christ that working in silence they should earn their bread. This is a good and holy way: follow it.

20] The Rule of Carmel continues with an explicit reference to the second letter of St Paul to the Thessalonians. Here with the aid of Paul Albert insists that the hermits on Mount Carmel should engage in ‘some work’. What does this entail? Paul’s text and St Augustine’s later interpretation of it put a clear emphasis on manual work (see his De opere monachorum, PL 40, 547-582). Undoubtedly the work of the early Carmelites on Mount Carmel was most probably manual. However, when they came to settle in Europe in 1247 it was likely they saw work in terms of the apostolate, in terms of preaching, teaching and caring for the sick and needy. Idleness was always a temptation for hermits, and so Albert repeats the hard quotation from Paul used in many monastic rules. For the remainder of the chapter Albert commends the vision of Paul in 2 Thessalonians to the early Carmelites. He says, echoing the words of Isaiah 30:21, ‘This is a good and holy way: follow it.’ Just before the end, in the penultimate sentence, we have a pre-echo of the succeeding section of the Rule which treats of silence.

21] The apostle therefore recommends silence, when he tells us to work in it; the prophet too testifies that silence is the promotion of justice; and again, in silence and in hope will be your strength. Therefore, we lay down that from the recitation of Compline you are to maintain silence until after Prime the following day. At other times, though silence is not to be so strictly observed, you are to be diligent in avoiding much talking, since scripture states and experience likewise teaches, sin is not absent where there is much talking; also he who is careless in speech will experience evil, and the one who uses many words harms his soul. Again the Lord says in the gospel: an account will have to be given on the day of judgement for every vain word. Each of you is to weigh his words and have a proper restraint for his mouth, so that he may not stumble and fall through speech and his fall be irreparable and fatal. He is with the prophet to guard his ways so that he does not offend through the tongue. Silence, which is the promotion of justice, is to be diligently and carefully observed.

21] The Carmelite Rule promotes silence for a number of reasons, some practical: gossip or chatter can lead to sin; night silence allows others to sleep. But the key point is that it promotes justice, that is, right relations with God and others. The Carmelite mystical tradition is unanimous in its insistence on silence. Associated with it are such ideas as happiness, calm, ease, quite, repose, serenity, tranquility. St Therese of Lisieux declared ‘Silence is the language of heaven’ (Letters 163: 20). Our modern world leaves little room for silence. Those who live in towns or near main roads become almost immune to the roar or steady hum of traffic. If the word ‘silence’ is not very frequent in the Bible, the corresponding word, ‘listen’ is everywhere. One point of being silent is to listen within to our own being, and more importantly to listen to God who may be speaking to us. The Rule of Albert lays down strict rules regarding the observation of complete silence on the part of Carmelites and emphasises just how injurious careless speech can be both to the person speaking and to others. The Rule is a call to each of us to rediscover the importance of silence in our lives.

22] You, Brother B, and whoever is appointed Prior after you, shall always keep in mind and practice what the Lord said in the gospel: Whoever wishes to be greater among you shall be your servant, and whoever wishes to be first must be your slave.

22] At this point Albert begins to draw the Rule to a close, once again along the lines of a letter. He addresses the prior by name ‘Brother B’. Albert also looks to the future, pointing to the eventual succession that will take place with the appointment of a new prior. Referring to Matthew 20:26-27 he, once again, points to the radical and counter-cultural nature of the Carmelite understanding of leadership. In allegiance to Jesus Christ, and following his example, Carmelite leadership is one of service. The prior is first among equals and leads through service. This gospel ideal of authority is relevant still for Church and secular leaders today.

23] And you too, the other brothers, are humbly to honour your prior, and rather than thinking about him, you are to look to Christ who set him as head over you; he said to the leaders of the Church, whoever hears you hears me, and whoever despises you despises me. Thus you will not be judged guilty of contempt, but through obedience you will merit the reward of eternal life.

23] The relationship between the prior and the brothers is such that it reminds all concerned of the primary aim of the Carmelite way: to live in allegiance to Christ. The prior to whom the other Carmelites promise obedience and fidelity is not the ultimate focus. Christ is the foundation and focus of the Carmelite life.

24] I have written these things briefly to you establishing a way of life for you, according to which you are to conduct yourselves. If anyone does more the Lord himself when he comes again will repay him. You are, however, to use discretion, which is the moderator of virtue.

Translation from Ascending the Mountain: The Carmelite Rule Today (The Columba Press, 2003)

24] Albert’s concluding chapter clearly echoes his own words in chapter 3: ‘Now then you have come to me seeking a formula of life according to your purpose, which you are to observe in the future.’ He has done what he set out to do. Albert’s Rule ends with a reference to the parable of the Good Samaritan in Luke 10. Luke says: ‘If you will have spent more, I shall reward you when I return’ (Lk 10:35). Following this, Albert says: ‘If anyone does more the Lord himself when he comes will repay him.’ Albert concludes encouraging the Carmelites to use discretion or discernment. In the Conferences of Cassian, a fourth century monk quotes the Abbot Anthony as saying: ‘Discernment is the mother, the guardian, and the guide of all the virtues.’ {Conferences 2:4)

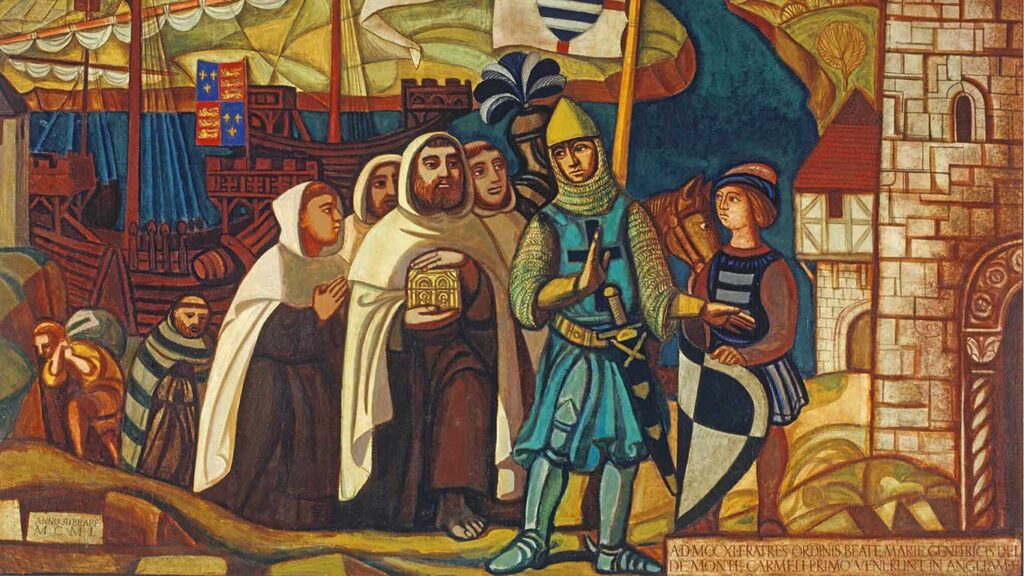

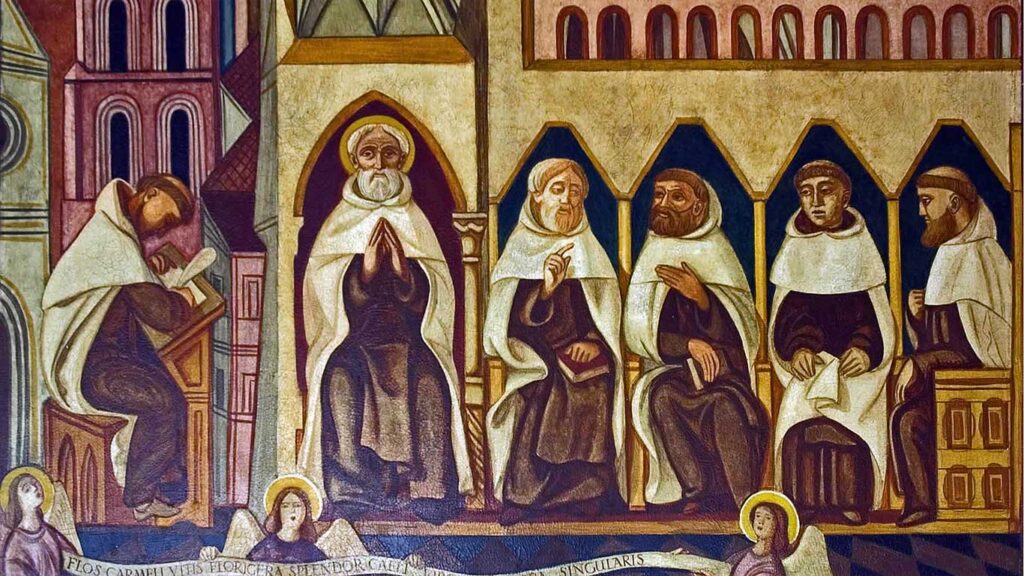

The image(s) featured in this section are courtesy of The Friars, Aylesford, Kent, where they are located.